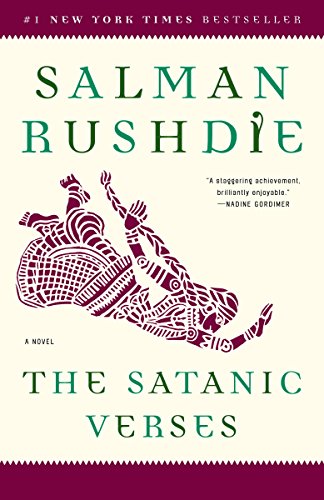

I was at university when Salman Rushdie published “The Satanic Verses”. I never read it; I had glanced at copy of his first book, decided it was not for me and so I certainly was not going to bother with something even obscurer. Then of course came the uproar; the outrageous incitement to murder issued by Ayatollah Khomeini, the book burnings and the years of hiding by Rushdie himself. But I also knew that blasphemy was not just a Muslim concept; until 2008, blasphemous libel was a criminal offence in this country and had been used by Christians.

Blasphemy can be considered as the act of making offensive and outrageous claims against God. It can cover a host of actions, from a mild invocation of the name of the deity during moments of stress to an deliberate attempt to offend and provoke. Some can be deeply upset when their beliefs are subject to ridicule and I would argue that we have a duty of care with our words not to gratuitously cause offence. But sometimes satire and irony are legitimate forms of debate, as a way of challenging and testing ideas. As a Christian, when I read that a particular journalist “has no time for religion”, my reaction is often to read more to spot the flaws in his or her argument, certainly not to retreat into outrage and offence.

Blasphemy is dangerous as it can raise particularly strong emotions; it is easy to imagine that God is on our side, we are engaged in a holy war against the blasphemer. The words of Jesus are particularly pertinent; his call to love our enemies, to pray for those who persecute us. His example is even more relevant; he was condemned to death for blasphemy by the religious authorities who were so sure that they were acting on behalf of God. How little did they know! Jesus’s response to those who killed him should surely be the basis of our response to those who offend us; “Father, forgive, they know not what they do”.